Buy vs Rent: The Overwhelming Financial Case for Renting in Expensive Markets

Let’s talk about everyone’s favorite question in real estate: is it better to buy or rent my home?

You’ve probably heard arguments on both sides of the debate. Those who argue in favor of homeownership tend to view rent as a waste of money that enriches the landlord (“it’s just flushing money down the toilet!”), and see homeownership as a way to build wealth long-term. They may also place importance on stability and peace of mind in their living situation.

But there are good arguments on the other side, too. Many people who rent would buy if they could afford to, of course, but that doesn’t apply to all renters — in fact, “millionaire renters” are a growing faction. Those who intentionally choose renting over buying may be focused on simplicity, flexibility, and avoiding debt. (And a different kind of peace of mind: not having to fix stuff when it breaks!)

I teach my coaching clients to be laser-focused on the numbers as investors. But the buy vs. rent decision is personal, situation-dependent, psychological, and complex. In other words, regardless of what the numbers say, it can come down to personal preference, to “feels”. What’s right for one person might be wrong for another person, even in similar circumstances.

In this article, though, I’m going to dive deep into what the numbers DO tell us. Taking all the personal stuff out of the equation, what’s left is the cold, hard math of the question — and the math reveals some truths that may surprise you.

Here’s what you can expect in this article:

I’ll take a thorough look at the financials of the buy-vs-rent question in three specific examples, and demonstrate the overwhelming financial case for renting if you live in an expensive area

I’ll share what I think is the BEST buy-vs-rent calculator out there, so you can use it to run your own numbers

I’ll explain what may seem like an insane contradiction in my own life: I own 25 rental properties, but NOT my primary residence

Financial factors in the buy vs. rent decision

As a starting point, let’s agree on the terms of the discussion and put some structure around the costs you’ll experience as a renter vs. those you’ll experience as a homeowner.

Initial Costs

As a renter, your initial costs are pretty limited — usually, you’ll just owe a 1-month security deposit. But as a buyer, you’ll have your down payment and closing costs, a much bigger chunk of change.

Ongoing Costs

If you rent, your ongoing costs are again pretty simple: it’s your monthly rent.

Calculating ongoing costs for a homeowner is a little trickier though — and it’s here that a lot of the buy-vs-rent discussion goes off the rails. Why? Because it’s easy to forget about some of the categories of homeowner expenses. Here’s the full, real-life list:

Mortgage (principal & interest)

Property taxes

Insurance

HOA or condo fees (if applicable)

Maintenance, repairs, and improvements

Opportunity Costs

This is the elephant in the room that is most frequently ignored when people think about buying vs. renting.

Usually you’ll hear arguments like this: “My parents/grandparents bought their house for $X in the year 19XX, and now it’s worth 30 times that! Man, they made a killing. Homeownership is clearly a good investment and the best way to build wealth.”

But we can’t understand if this is a good investment in a vacuum. We have to ask whether it was a good investment compared to the alternative, which would be renting a similar property over that entire period. Remember those high initial costs to buy — your down payment and closing costs? When you rent, you can take all that money and invest it somewhere else. This is HUGE, as we’ll see in the real-life examples below.

Closing Costs

There’s a final piece to the puzzle, which is the cost to access the wealth accumulated in a property over time.

As a renter, you don’t accumulate any wealth, but you also don’t have any costs going out the door. (In fact, you get your security deposit back.) As a buyer, your closing costs will eat into the equity gains you made over time, usually to the tune of about 6% of the sale price.

The best buy vs rent calculator is…

Based on the four cost categories discussed above, that’s already a lot to calculate! And I didn’t even mention the most complicated parts, which are:

Building in assumptions about the long-term growth of home prices and various costs

Incorporating a presumed rate of return in the Opportunity Cost calculation

Layering in various tax implications, such as the deductibility of mortgage interest and property taxes, and the capital gains tax that will be due upon sale of your home

I’m always fond of building my own calculators for these kinds of analyses, as it ensures that all factors are correctly incorporated — many online calculators are bare-bones, omit important factors, and are therefore pretty useless. That’s why I built my own Rental Property Analyzer (available for free download, btw), as well as a complex model to compare expected returns investing in Stocks vs. Rental Properties.

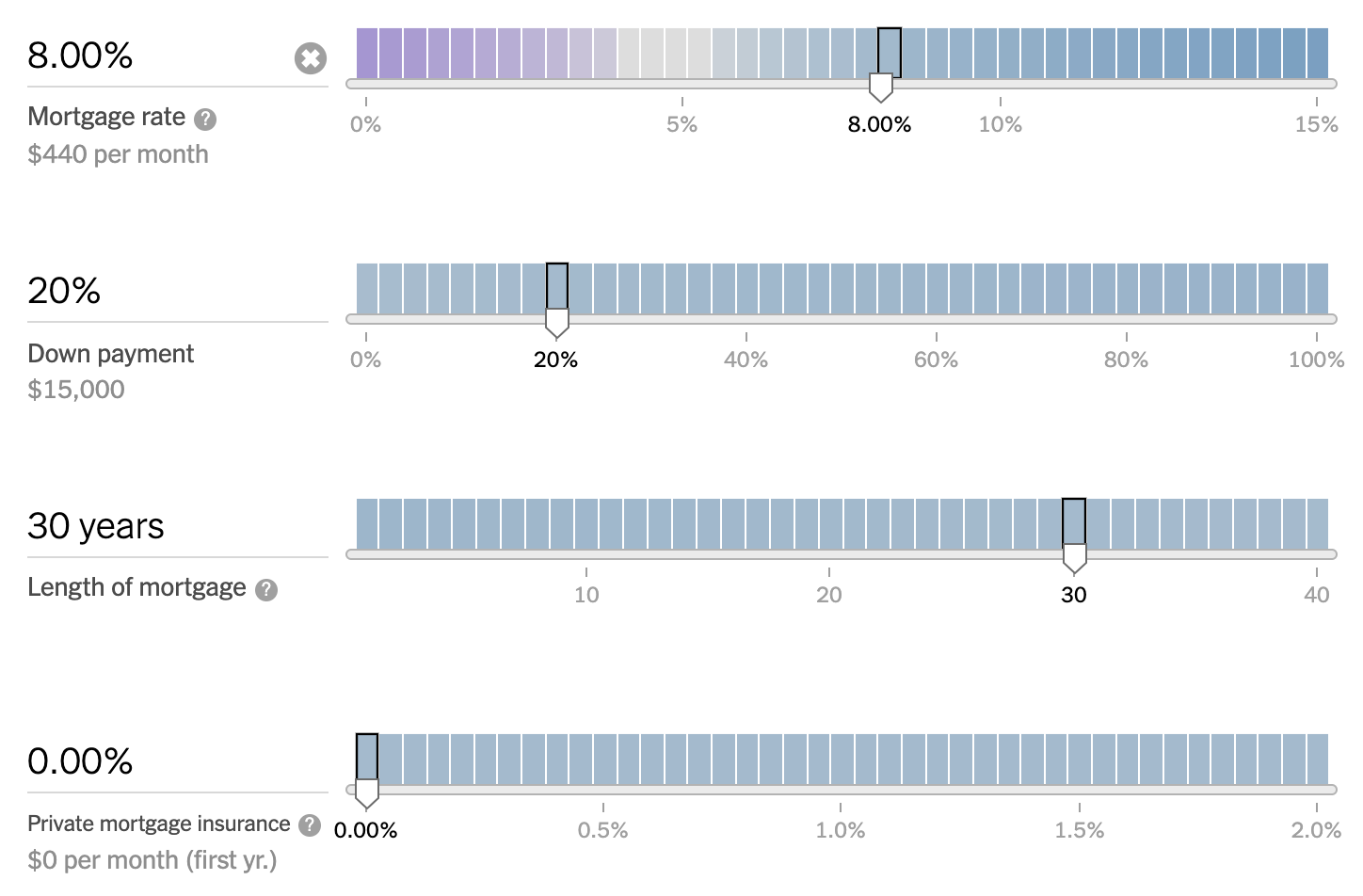

But in this case, there’s already a REALLY good buy vs. rent calculator out there: the one published by the New York Times. It incorporates ALL of these factors in exactly the way that I would — so no need to build my own!

I’ll be using that buy vs. rent calculator for the rest of this article as we explore some real life examples. Here is a free link to access the calculator, even if you’re not a NYT subscriber.

So — enough chit chat, let’s look at some numbers!

Buy vs. Rent Example #1: My Parents’ House

Remember that common argument I mentioned earlier where someone points to their parents’ or grandparents’ house as evidence for what a lucrative investment homeownership can be?

Well, I could do the same thing. My parents bought their house in 1973 for $38,000. It’s the house I grew up in, and they still live in that same house today. They’ve taken great care of it, and thanks to their improvements it’s a much bigger and better property today than when they bought it over five decades ago.

Today, the house is worth about $600K. So this was clearly better than renting for 50 years, right? Let’s find out.

Because of some limitations of the calculator, I’ll have to tweak the initial inputs a bit:

$75,000 is the lowest purchase price they’ll let me input, so I’ll use that.

Because of that, we’ll need to adjust the initial rent amount as well. Today’s rent potential is $4,000, which means that the purchase price is 150x the rent. Applying that same ratio, I’ll use $500 as the initial rental value of the house.

The calculator only has a 40-year time horizon, so that’s as far as we’ll be able to run the simulation.

Otherwise, we’ll plug in the exact values from the 1973-2024 — no need to use averages or projections since we have the data from those years. The rest of my initial inputs look like this:

Mortgage Details

Closing Costs

Taxes

Growth Rates

Maintenance & Fees

A few notes of explanation about the inputs I used:

Mortgage rates in the second half of 1973 were between 8% and 8.5%. Rates didn’t fall consistently below 7% until 2001 — almost 30 years later. In reality, my parents refinanced this loan several times over the last 50 years (which would come with transaction costs, and the associated opportunity costs, each time, and therefore be DISadvantageous to buying in this calculation) — but for the purposes of this analysis, we’ll leave that out. Using 8% for the life of the loan seems more than fair, given what rates actually were in this period.

The growth rate numbers are based on the true average annual figures from the 1973-2024 period; the investment returns represent average annual returns from the total stock market from that period.

The property tax rate is realistic for this neighborhood in New York State.

The maintenance/renovation figure is higher than the default in the calculator, but probably still vastly UNDERSTATES the amount of money my parents put into the property over the years.

Using these inputs, and after running the simulation for 40 years, here’s what the buy vs. rent numbers look like:

I included the NYT’s full explanation of those 4 cost areas, because the way they’re presented — particularly the last two — can be confusing. Their explanation for Net Proceeds is helpful: because this is a calculation of COSTS, a negative figure here is good. In this case, my initial investment to buy the home was $18,000, and my net proceeds from the sale 40 years later were $590K. Not bad at all! That $590K reduces the total costs in the Buy scenario.

Opportunity costs is a bit confusing because they calculate this not just on the initial costs (which makes sense), but ALSO on the ongoing/recurring costs. Of course, you can’t avoid some kind of monthly living cost…you have to live SOMEWHERE, after all. But for the purposes of the calculator, it’s really the DIFFERENCE in recurring costs that will drive an opportunity cost for the option that’s more expensive on a monthly/recurring basis; if the recurring costs are equal, then the opportunity costs are equal.

But the opportunity costs of the initial payments are certainly NOT equal. Think about it this way: to buy the house initially costs $18,000, while renting only costs $500, for a difference of $17,500. Were you to invest that $17,500 into the stock market for 40 years, using the average 10.9% rate of return during this period, you’d have holdings worth nearly $1.1M — which matches nearly exactly with the DIFFERENCE between the opportunity costs in the renting column vs. those in the buying column.

Since the ongoing costs of buying and renting in this particular scenario are quite similar, it really reduces down to this at the end of 40 years:

If you buy, you end up with a house worth $638K

If you rent, and instead invest the down payment, you end up with a stock portfolio worth $1.1M

That’s why the calculator says that renting “saves” you $526K; stated a different way, renting would produce an additional $526K in wealth. And this is almost entirely due to the opportunity cost of investing the down payment in the house, rather than into higher-yielding assets.

Hopefully the structure of the math makes sense now. Let’s dive into some other examples!

Buy vs. Rent Example #2: My Move to Virginia

If you subscribe to my newsletter, you know that I recently moved to northern Virginia after nearly two decades in New York City. I was already renting in NYC — in fact, selling my primary residence and becoming a renter is what feed up the capital for me to start building my Memphis rental portfolio in the first place. (A great example of the opportunity costs of homeownership!)

But now I’d be establishing a new home in a new place. So I was faced with the question once again: should I buy or rent? Spoiler alert: I decided to rent. But let’s look at the numbers to see why.

To be close to family, we wanted to be in Falls Church, which (like much of northern Virginia) is a pretty expensive place to live. We were looking for a 2-bed/2-bath place in a large full-service building, such as a rental building or condo building. After our rental search, we ultimately decided on a building and unit that would cost $4,400 per month, which was one of the MOST expensive options we found — not as much as New York City, certainly, but still very steep. That’s the number I’ll use for the initial rent amount in this example.

To find a similar condo — same quality, same central area — we’d have to spend at least $800K. (Here’s a representative listing that was active at the time of writing.) So I’ll use that amount for the “buy” amount in this example.

I’ll also use a shorter 10-year time horizon in this example; I expect we’ll be here for at least that long, but I’m less sure about what will come after that. Here are the rest of my inputs:

Mortgage Details

Closing Costs

Taxes

Growth Rates

Maintenance & Fees

A few notes of explanation about these inputs:

Mortgage rates are currently around 6%, so that’s what I used.

I used the same growth rate as in the previous example, simulating the average stock market returns over the past 50 years.

The property taxes and monthly common fees are the exact figures from the comparative condo listing I used.

The maintenance/renovation figure is lower, since this is a condo and we’d therefore expect less expenses over the long-term than a single-family home.

One more point here: if I were running these numbers, I wouldn’t use 10.9% as my investment return rate. Why not? Because I know I can easily achieve better than that with rental properties. This property, for example, will achieve 14% total ROI on my invested dollars, a combination of cash flow, mortgage principal reduction, and 2% home price appreciation. And this house is unspectacular — many of my other properties achieve quite a bit more. I also proved in my Stocks vs. Rental Properties article that rentals pretty easily outperform the stock market in the lon run.

Therefore, I’d probably use 15%, rather than 10.9%, to correctly simulate the opportunity cost of making a down payment instead of investing those same dollars into rental properties.

Here are the results of this example — either way, renting is once again the MUCH better financial choice:

With 10.9% investment return rate:

With 15.0% investment return rate:

And of course, the situation doesn’t get better for Buying if you extend the time horizon past 10 years: at 20 years, renting increases your wealth by $1M-$2M compared to buying (depending on which rate of return you use), and at 30 years, the difference is $3M-$10M.

As you can see, compounding is an extremely powerful force, which makes the opportunity cost of a down payment on home much higher than most people realize.

So — why do I own 25 rental properties, but rent my primary residence? Because the numbers clearly tell me that this is optimal. In fact, it isn’t even close. (Plus, I really like not having to mow the lawn or fix stuff that breaks — bonus!)

Buy vs. Rent Example #3: A Counter-Example

So far we’ve look at two examples of renting vs. homeownership, and in both cases the needle points strongly toward renting as the preferable financial choice.

But what about for ME, you may be asking? Well, if you’re reading this, there’s a pretty good chance you live in a HCOL (high cost-of-living) area, where home prices are above the national average. If that’s the case, you’re going to find the same thing when you run your own numbers in the calculator: from a strictly financial standpoint, you’d be better off renting in HCOL areas — usually MUCH better off.

But are there exceptions to this? What about where home prices are cheaper?

Let’s take a look at one of my investment properties to find out — in fact, let’s look at this same one I alluded to earlier, the one that was projected to get 14% total ROI. This turnkey home cost me $121K, and it rented for $1,100. At the time I bought the property, I got a 6.75% interest rate on my loan (I could get lower at the time of writing, which would move the needle further toward buying.)

Here are the rest of the inputs for this example, all taken directly from the actual figures for this property where applicable:

Mortgage Details

Closing Costs

Taxes

Growth Rates

Maintenance & Fees

So…will this house be any different? In fact, it’s a LOT different, mostly due to how much cheaper the house is to buy relative to how much is costs to rent. (Investors commonly refer to this as “price-to-rent ratio”.)

With these inputs, here are the results of this example, using the same two rates of return assumptions, and over several different time horizons:

With 10.9% investment return rate:

With 15.0% investment return rate:

In this case, it would be financially preferable to buy. If I were looking to live in this neighborhood, in a house like this one, then we’d reach the OPPOSITE conclusion than we reached in the first two examples. Even when we assume we could achieve 15% investment returns if we invested our down payment elsewhere, it’s still cheaper to buy because the ongoing monthly costs are so much lower (see the “Recurring costs” line in the results above — it’s a huge difference.)

Which of course makes sense when you think about it. These are the types of homes I buy as an investor because I calculate that I can make a healthy monthly profit as an owner — in other words, I can achieve positive cash flow. Another way of saying this: the tenant is paying more per month than I am. And when that’s the case, you’d rather be the owner than the tenant.

But is buy vs. rent really just about the numbers?

No, certainly not. As I often tell my coaching clients, the decision to buy or rent is complicated and personal. The financials side of the decision is just one aspect, and might not be the most important one for you. You might care about stability, the peace of mind of having your own space and being able to do what you want with it, staying in a specific school district, or other considerations.

Case in point: my first example above was my parents house, which they bought in 1973 and where they still live today. As we’ve already seen, despite the house increasing in value from $38K to ~$600K over those 51 years, renting would have been a better financial decision. And they admit as much — when I’ve talked to them about this, they acknowledge that the house has been a money pit. My financial example very likely understates the amount of money the spent on the house over that time, including numerous major improvements (an addition; finishing the basement; building a large deck; installing an in-ground pool; fully renovating kitchen & bathrooms at least once; installing central air conditioning; and much more.)

So do they regret it? Not in the slightest. They’d probably explain it like this: “It’s OUR home, set up exactly the way we like things. It’s comfortable and familiar. We take pride in the improvements that we’ve made to the house. And it’s full of memories — this is where we lived most of our lives, where we raised our kids, and where we still gather our extended family on holidays and important occasions. It was worth the cost.”

And that’s hard to argue with — it makes perfect sense. But they don’t fool themselves into thinking their house was a “good investment”. It absolutely was not, strictly in financial terms.

In fact, you should NEVER think about your primary residence as an investment. It just isn’t — or, at best, it’s a bad one. There will always be many better ways to invest money. Instead, look at it this way:

You need a place to live, and that will cost you money whether you buy or rent.

An honest accounting of the costs shows that it’s far better to rent in places where homes are expensive.

Nevertheless, you might choose to buy (or rent) for non-financial reasons.

Conclusion

The buy vs. rent debate will no doubt rage on forever, and different people will value different aspects of homeownership or renting. But strictly looking at the numbers, you now have some data-driven insights into the financial side of that question:

In high cost-of-living areas, the financial case for renting is overwhelming.

This is primarily because of the opportunity cost of NOT investing your down payment into higher-yielding assets.

Anecdotal stories about huge home price appreciation over decades (“look at my parents’ house!”) are misleading, and obscure the real costs of homeownership.

Only in low-cost-of living areas is there a financial case for buying.

You should not view your primary residence as a (financial) investment of any kind, because it’s not.

About the Author

Hi, I’m Eric! I used cash-flowing rental properties to leave my corporate career at age 39. I started Rental Income Advisors in 2020 to help other people achieve their own goals through real estate investing.

My blog focuses on learning & education for new investors, and I make numerous tools & resources available for free, including my industry-leading Rental Property Analyzer.

I also now serve as a coach to dozens of private clients starting their own journeys investing in rental properties, and have helped my clients buy millions of dollars (and counting) in real estate. To chat with me about coaching, schedule a free initial consultation.